There are many careers that seem like they have existed since the dawn of time, none more so than the humble artist. As society progressed from the agricultural revolution to the 21st century, the tools evolved, but the need to create has stayed the same. Now, the modern artist faces a new challenge that threatens the integrity of their craft. AI-generated media is everywhere, flooding social feeds with photos, paintings, videos and even ‘people’ that don’t actually exist. At first, it was easy to spot. The people pictured with extra fingers and warped faces would always make me do a double-take, while the comical videos were a lot less convincing. But after a steep learning curve and a lot of trial and error, AI art has become almost indistinguishable from human-made art. As the line between fantasy and truth blurs, what does this mean for the modern artist and their practice?

Jason Allen and the Copyright Debate

My first introduction to AI art came in 2022, when I read about Jason Allen, who won first place at the Colorado State Fair’s digital art competition. To much of the internet’s shock and outrage, Allen’s winning piece titled ‘Théâtre D’opéra Spatial’ had been created using Midjourney, a generative AI tool that turns text prompts into images. Although it took him writing 624 different prompts to refine the final image, technically no rules were broken. The category allowed ‘any artistic practice that uses digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process’, and Allen had done exactly that. Even though he disclosed his use of Midjourney, many accused him of being a fraud, arguing that such tools ‘scrape’ existing images from the internet to produce derivative work without the original artists’ consent. Allen’s win marked an early milestone for AI-generated art, raising uneasy questions about authorship and copyright.

He later applied to the US Copyright Office to claim royalties for use of his work. The application was denied, as the image lacked sufficient human creativity to qualify as an ‘authored’ piece. As a former graphic designer, the irony of copyrighting copied work isn’t lost on me. Despite Allen’s greed, I was relieved by the decision, though it raises further questions. What counts as ‘enough’ human input in AI-generated work is not quantifiable, it is judged by the quality of contribution instead. This creates a grey area, leaving room for subjectivity around who gets the right to profit and who does not. These rules also vary from country to country, adding to the uncertainty. I can’t help wondering what the tipping point will be for governments and Big Tech to shift their stance. Most likely when it best serves their financial and political interests.

In the UK, debates over AI are intensifying as the government proposes allowing tech firms to train their AI models on copyrighted works, with an option for creatives to opt out. Artists argue that this shifts the burden onto them, is nearly impossible to enforce and threatens their livelihoods. High-profile opponents like Elton John and Kate Bush, along with 48,000 signatories, have condemned the proposal. For now, the House of Lords has repeatedly blocked the bill, demanding greater transparency from AI developers.

The Cost of Instant Creativity

If you were online in March, you probably remember the viral Studio Ghibli trend. ChatGPT’s new update let people transform anything from selfies to movie stills into the style of their favourite cartoons, including that of the Japanese animation studio behind classics like ‘Spirited Away’. Maybe you even made one yourself. I’ll admit, it was fun to see countless animated characters on my feed. The problem, though, is that it went against everything Studio Ghibli stands for. The co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, known for his hand-drawn approach, famously criticised AI as early as 2016, stating ‘I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself. I feel like we are nearing the end times. We humans are losing faith in ourselves’.

There is something deeply disheartening about a style that took years to refine being turned into a template. It reflects the microwave generation we live in, which often rewards instant results over the patience and care required to produce timeless work. At the core of this issue is the devaluation of human-made art. Generative AI tools do not require a Fine Art degree or 10,000 hours of practice to create images. All you need is a phone, an AI program and perhaps a quick YouTube tutorial. This dramatically lowers the barrier to entry, oversaturating the internet with content and skewing the digital art market. GSMA reports that over half of the world’s population (4.3 billion people) now own a smartphone, while around 10% of the world currently use ChatGPT. As a result, existing artists may see a decrease in bookings as potential clients choose AI alternatives or feel entitled to negotiate lower prices. Emerging artists may hesitate to share their work online, worrying it could be used to train AI without permission or lead to false accusations of AI use.

Reviving the human touch

Still, it might not be all doom and gloom. Speaking of photography in 1859, French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire declared, ‘From today, painting is dead!’. But the invention of photography didn’t kill painting, it made way for abstract movements like Expressionism and Surrealism, as artists were freed from the need for precise visual representation. Similarly, the arrival of high-resolution cameras eventually led to a resurgence of grainy low-resolution photographs on social media, and a renewed interest in film photography. I know I’m not the only one who picked up a disposable camera this summer. With every new invention, society finds a way to restore the equilibrium.

Ralph Lauren’s Wimbeldon stop-motion by Andrea Love | Instagram

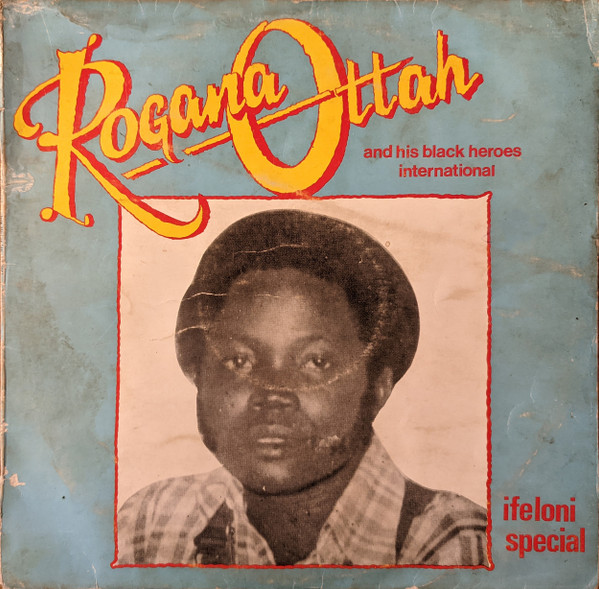

In the same way, I think AI art is sparking a renewed appreciation for physical arts and true craftsmanship across disciplines. I’ve noticed it especially in fashion advertising. French luxury house Hermès recently commissioned around 50 artists for their social media posts, featuring sculpture, pen illustrations and intricate paper cut-outs, to the delight of their followers. Ralph Lauren also commissioned stop-motion animator and fiber artist Andrea Love to create a beautifully charming Wimbledon post. In the event space, Jojo Sonubi, known as ‘a cultural architect for the Black British experience’ has reshaped event poster design with hand-drawn elements and time-lapse videos showing his process. Despite the rise of AI-generated songs and virtual artists, even the music industry is embracing work that celebrates human creativity: Afrobeats icon Olamide recently licensed a piece from Nigerian artist Uzo Njoku for his single ‘Kai!’ featuring Wizkid. Njoku’s cover art referenced both Sean Paul’s ‘Get Busy’ music video and a 1983 Nigerian album cover. The emotion that emanates from such context-rich, artist-driven work is unmatched. I find it carries a soul that AI can’t quite replicate. As brands, musicians and cultural figures align themselves with human-made art rather than ‘AI slop’, they gain the respect of their audiences while investing directly in artists and putting them on a global stage.

There is still a general public skepticism of AI, particularly when people are being sold a product or service. It seems like the perfect opportunity for artists of all disciplines to double down on their craft, for the survival of traditional arts but also the integrity of their own practice. The beauty of a rapidly changing world is the opportunity for new approaches. What will be your contribution?

Leave a comment