What comes to mind when someone mentions a ‘red flag’? For most people, it signals danger, and symbolically it describes an undesirable trait in a person. Either way, it is a warning of what’s to come, inciting fear and caution. In contrast, a white flag communicates surrender or a plea for mercy, most often in war. Throughout history, flags have expressed identity, including status, nationality, race and community. Their colours and shapes are designed with intention, carrying visual meanings without the need for language. Black History Month is no different.

Origins of Black History Month in the United States

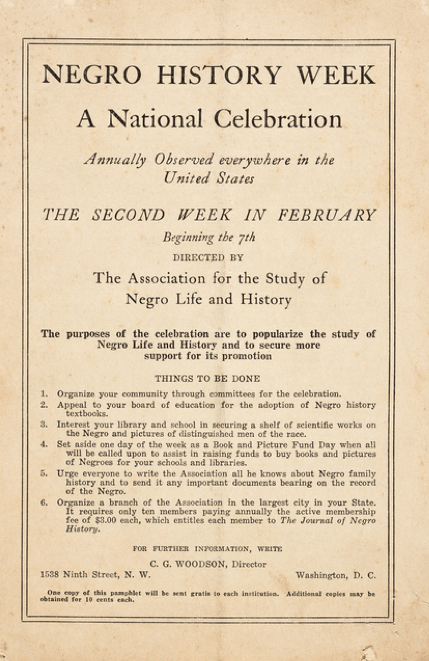

Born in 1875 as the son of formerly enslaved parents, Carter G. Woodson became the second African American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, specialising in History. Despite his academic standing and his membership to the American Historical Association, he was barred from attending their conferences. African American contributions were routinely overlooked in the white-dominated profession, and in response, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in Chicago. Just over a decade later in 1926, he launched Negro History Week.

Woodson intended it as a national celebration to popularise the study of African American history, to occur during the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of former president Abraham Lincoln and activist Frederick Douglass, who were both influential abolitionist figures. Over the years, the celebration often strayed from its origins, as is typical of many cultural events. Opportunists sought to profit from the new public interest in Black history by rushing to sell books and deliver lectures on the subject, with little knowledge.

Nonetheless, from the 1940s onwards Black history took root in the educational curriculum, advancing social change. Eventually, the week-long observance expanded into a month, and in 1976 (fifty years after the first celebration) the ASNLH officially changed ‘Negro History Week’ to ‘Black History Month,’ observed every February in the United States today.

The Birth of Black History Month in the United Kingdom

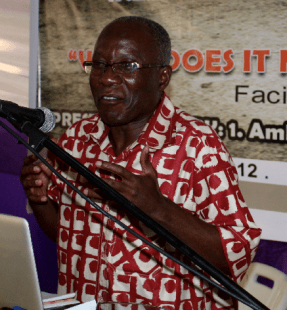

‘Mum, why can’t I be white?’ seven year old Marcus asked. Across the Atlantic, many Black children were grappling with an identity crisis in the United Kingdom. It was the 1980s, and the mother in question sorrowfully recounted her son’s question to a colleague. This prompted the colleague to investigate by speaking with children across London. They were surprised to learn that many were embarrassed to be associated with Africa, recalling that some Ghanaians tried to mimic being Afro-Caribbeans, while some Afro-Caribbeans took offense to being referred to as African. The man in question was Akyaaba Addis-Sebo, who had arrived in the UK from Ghana as a refugee in 1984. At the time, he worked within the Ethnic Minorities Unit of the Greater London Council. Motivated by his findings, he established an annual celebration of Africans and people of African descent in Britain. In 1987, the first Black History Month in the UK took place.

The Colour of Resistance

This year’s Black History Month theme in the UK is ‘Standing Firm in Power and Pride’. Last year it was ‘Reclaiming Narratives’. While the theme changes annually, the red, yellow, black and green branding has become a consistent marker of its visual identity. Yet in its early years, Negro History Week had no signature design direction to distinguish it from other movements. The booklets, posters and bulletins were usually printed in black and white, as well as most surviving photographs. Most notably, there was no official flag uniting the cause.

Remember the young boy named Marcus? His mother had deliberately named him after Marcus Mosiah Garvey, the Jamaican political activist. Garvey and members of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) designed the Pan-African flag in 1920, a unifying symbol for people of African descent across the world. Its creation was a direct response to a racist song that became popular in 1900, titled ‘Every Race Has a Flag but the Coon’. The flag’s design consists of three horizontal stripes of red, black and green. The UNIA-ACL published a book explaining their significance:

‘Red is the color of the blood which men must shed for their redemption and liberty; black is the color of the noble and distinguished race to which we belong; green is the color of the luxuriant vegetation of our Motherland’.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when these colours became associated with Black History Month, but they have since formed a powerful visual language used in official branding. Yellow was a later addition, derived from the Ethiopian flag. As Africa’s oldest independent nation, Ethiopia successfully resisted colonisation during the ‘Scramble for Africa’, and so the colour yellow came to symbolise hope, wealth, optimism and justice.

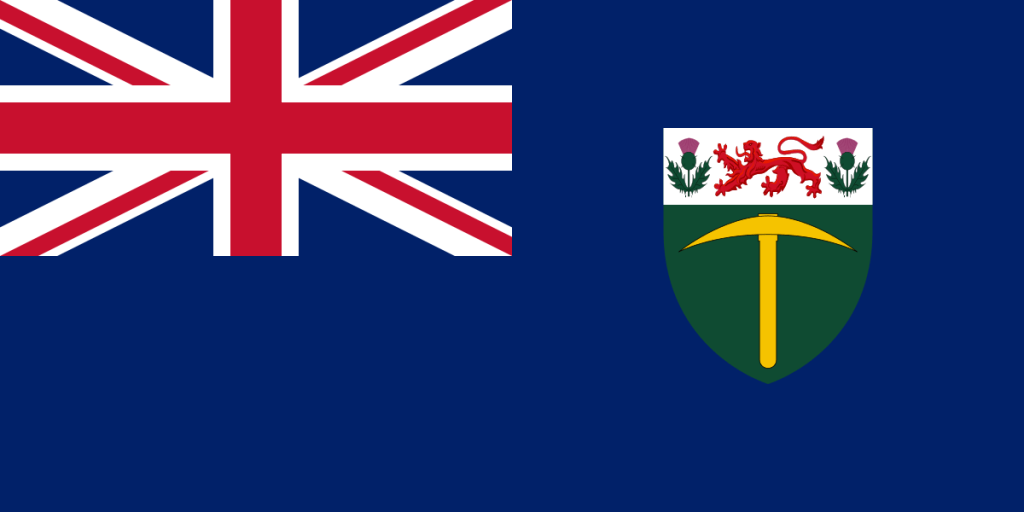

Under colonial rule, many countries were forced to adopt flags featuring European emblems such as the Union Jack. Visually, these flags asserted dominance, projecting the coloniser’s identity while erasing African and Caribbean symbols. In countries like Barbados and Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia), the colonial designs showed little interest in balance or integration. The stamp-like placement of European flags was reminiscent of branding cattle, where a hot iron sears the skin to leave a permanent mark of ownership. Similarly, slave owners branded enslaved people to assert control. Clearly, the design of colonial flags illustrated the brute force of colonisation and the treatment of Africa and the Caribbean as commodities to be exploited.

After gaining independence, several nations redesigned their flags by adopting Ethiopia’s palette of red, green and yellow as a visual tribute to the country’s history of resistance.

Flags in politics and protest

The lyrics ‘When I get older, I will be stronger, they’ll call me freedom, just like a waving flag’ ring in my ears with nostalgia every few years. They come from K’naan’s song ‘Wavin’ Flag’, which became a global hit as Coca-Cola’s official song for the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Originally written about Somalia and aspirations of freedom, the song remains strikingly relevant in today’s political climate.

At Notting Hill Carnival, the streets are filled with vibrant Caribbean flags as a proud display of cultural heritage every August. That same month this year, hundreds of St George’s Cross and Union Jack flags began appearing across England, hung from lampposts, flown from houses and even painted on roundabouts. It was driven by the online campaign #OperationRaisetheColours, which supporters described as a show of national pride and patriotism, but many organisers had alleged ties to far-right groups. The association became more explicit when far-right activist Tommy Robinson adopted the flag as a rallying symbol at his ‘Unite the Kingdom’ protest in September 2025, where chants like ‘Send them back’ and ‘We want our country back’ were prominent. Over 40% of the British public saw the flag campaign as a political statement against immigrants (poll by ‘More in Common’) and many people of ethnic backgrounds were concerned for their safety.

Evidently, flags can carry different meanings depending on who displays them and where. Wearing a Palestinian flag pin on TV can lead to censoring and the loss of sponsorship deals, yet at a protest it can be embraced as a powerful symbol of solidarity. Whereas a Nigerian flag flown at the National Assembly building in Abuja may be seen as a symbol of corruption and failed leadership, yet a Nigerian flag in someone’s Instagram bio may be seen as a badge of cultural pride, signalling their connection to Nigeria’s music, creativity and humour. A flag’s meaning is never neutral or determined solely by its design. The same flag can symbolise unity for some and evoke fear for others, because its message is shaped less by colours and patterns and more by the people and movements who display it.

Visual Identities in Sound

The Black music industry has seen a recent rise in the use of flags as symbols of pride. Some artists highlight their home countries’ flags, such as Ghanaian-American artist Amaarae on her album cover for ‘Black Star’ (2025) and Rihanna in her HOMMEgirls shoot featuring the Barbados flag. In her music video ‘Sexy Soulaan’, African American artist Monaleo combines pro-Black lyrics with a visual display of multiple African and Caribbean flags alongside the Black American Heritage Flag, created in 1967.

However what stands out in the UK scene, is the shaping of a layered identity among Black British artists. Rachel Chinouriri chose to hang England flag bunting in her album cover for ‘What a Devastating Turn of Events’ (2024), reflecting on her experience of ‘the battle of being Black in Britain’ and music such as Jim Legxacy’s album ‘Black British Music’ contributes to the mediascape shaping this dual-cultural identity.

When I visited Somerset House to see ‘rituals: unionblack’ by Akinola Davies Jr, a flag flew high above the stage: a Union Jack recoloured in Pan-African green, black and red. At the time, I wasn’t fully aware of the history behind the colours, but they felt familiar and seemed to signal a reshaping of identity. So the next time someone asks you where you’re from, take a second to consider what you represent and the flag that speaks for you.

Reference List

- Pan-African cultural celebration, Black History Month UK site | https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/windrush-day-2019/red-white-blue-feathers-summer-rain/

- Portrait of Dr. Carter G. Woodson (ca. 1915),

Scurlock Studio Records Archives Center | https://www.nps.gov/cawo/learn/carter-g-woodson-biography.htm?ftag=MSF0951a18 - Negro History Week press release by Woodson, ASALH website |https://asalh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Black-History-Month-Timeline-General-Branding.pdf

- The ASNLH/ASALH 1925, ASALH website |

https://asalh.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Black-History-Month-Timeline-General-Branding.pdf - Black History Month 1987, Black History Month UK site |

https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/interviews/akyaaba-addai-sebo/ - Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, Black History Month UK site | https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/interviews/akyaaba-addai-sebo/

- All Hands In, Linkedin | https://www.linkedin.com/news/story/black-history-month-kicks-off-6644108/?utm_source=rss&utm_campaign=storylines_en

- BHM San Francisco, SF Examiner | https://www.sfexaminer.com/news/the-city/your-guide-to-black-history-month-events-in-san-francisco/article_de164008-de8e-11ef-8baa-8f6feaa913c2.html

- Pan-African flag NY, We Are Buffalo | https://wearebuffalo.net/black-history-figures-buffalo/

- Ethiopia flag, Wikipedia | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_Ethiopia

- Colonial Zimbabwe/SR flag, Wikipedia | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_Southern_Rhodesia

- Post-colonial Zimbabwe flag, Britannica | https://www.britannica.com/topic/flag-of-Zimbabwe

- Activists at Tommy Robinson rally, The Standard | https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/tommy-robinson-whitehall-london-metropolitan-police-laurence-fox-b1247570.html

- Notting Hill Carnival, The Guardian | https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/01/notting-hill-carnival-success-crime-rate-glastonbury-london-culture

- Amaarae ‘Black Star’ album cover, Wikipedia | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Star_(Amaarae_album)

- Rachel Chinouriri ‘What a Devastating Turn of Events’ album cover | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What_a_Devastating_Turn_of_Events#/media/File:What_a_Devastating_Turn_of_Events.jpg

Leave a comment