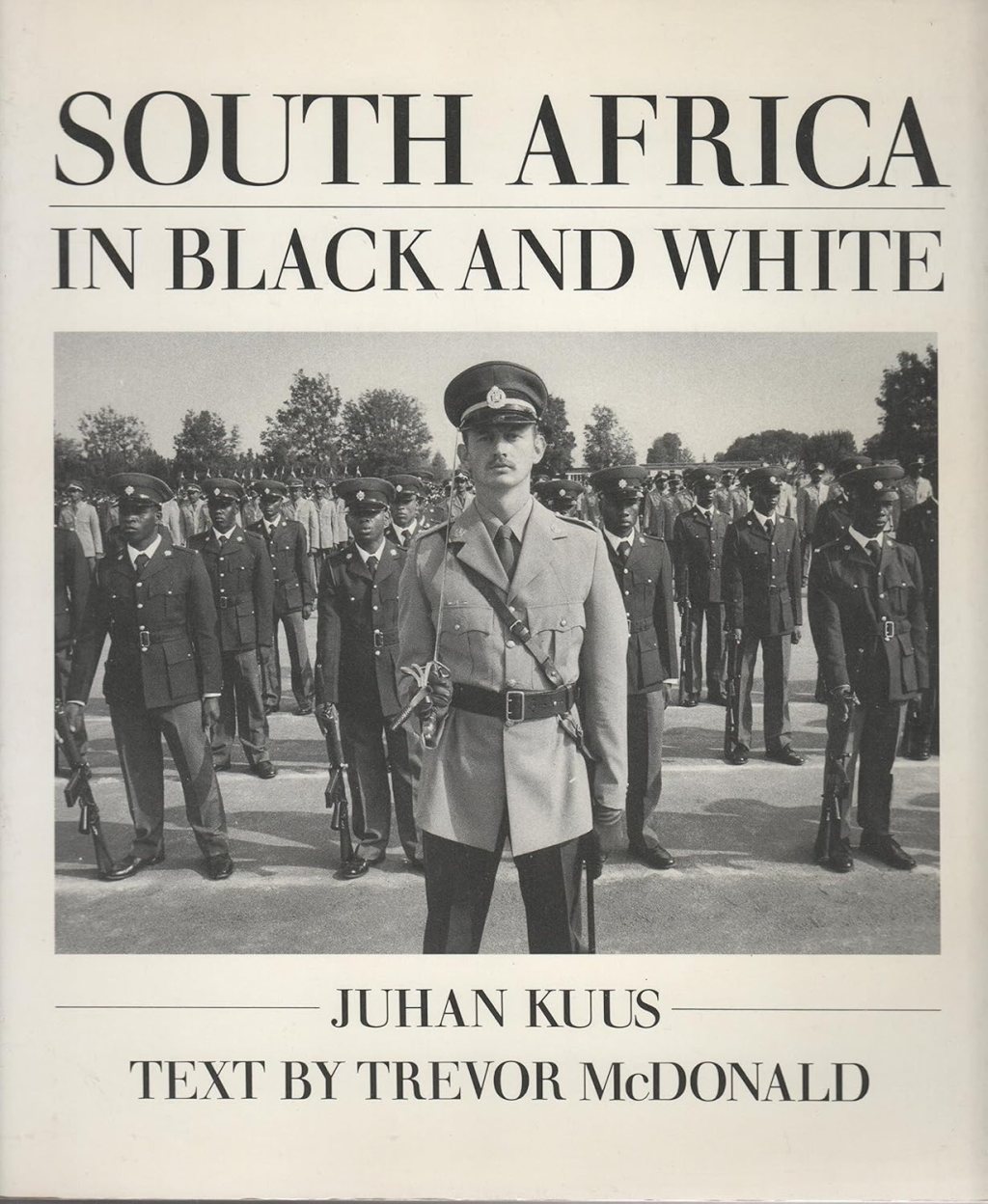

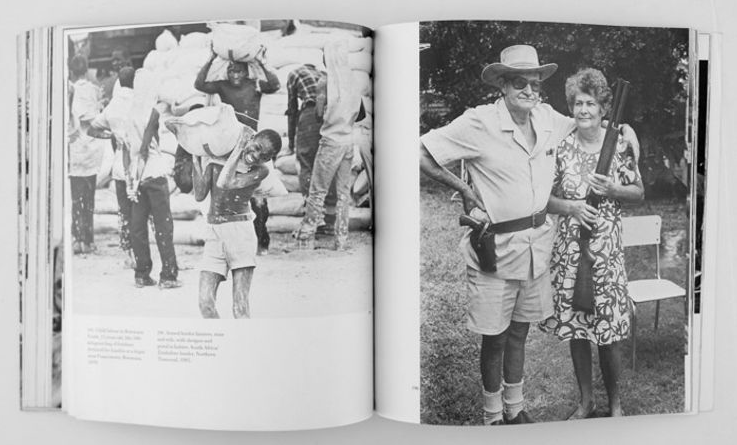

In 1987, when South Africa in Black and White was first published, its arrival was less a quiet documentation than a thunderclap of defiance. The collaboration between photographer Juhan Kuus and British journalist Trevor McDonald created an unflinching visual record of a country convulsed by oppression, yet pulsing with an indomitable will to survive. Within its pages lay stark evidence of apartheid’s daily cruelties—and, just as importantly, glimpses of lives that refused to be erased.

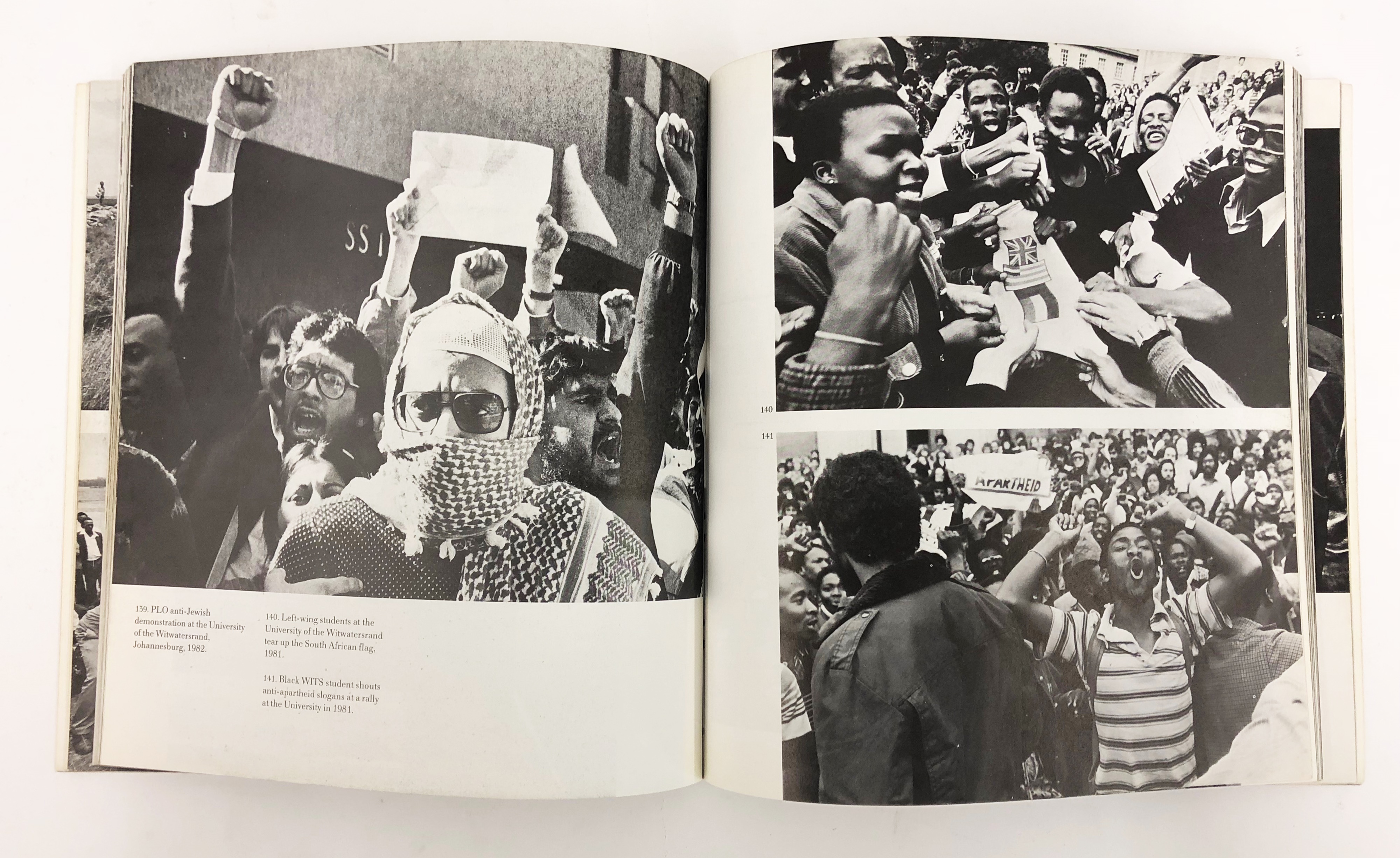

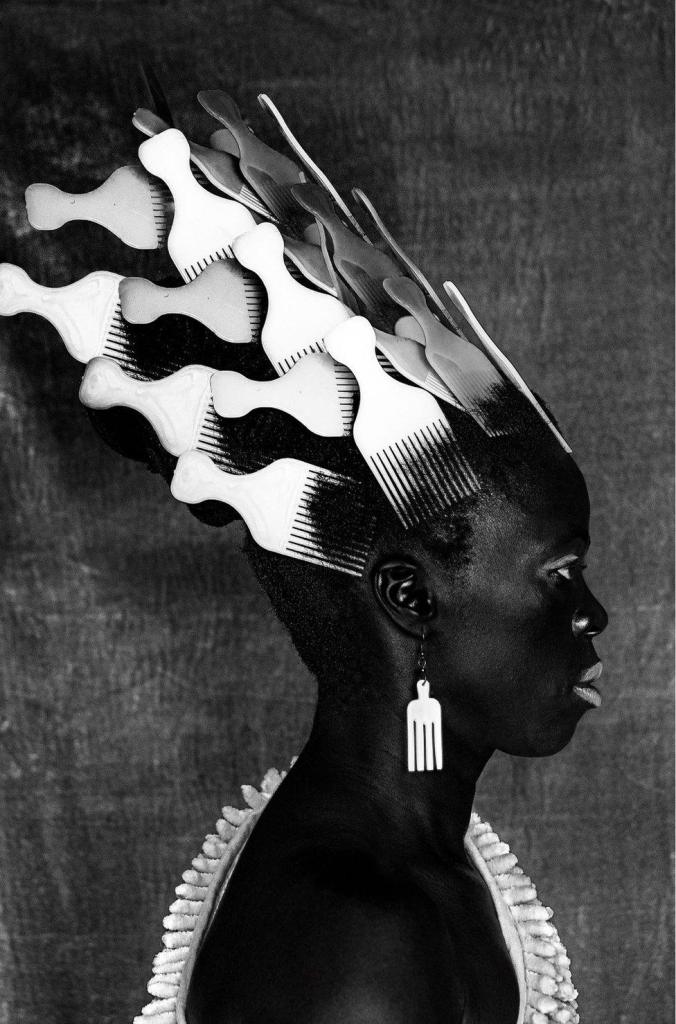

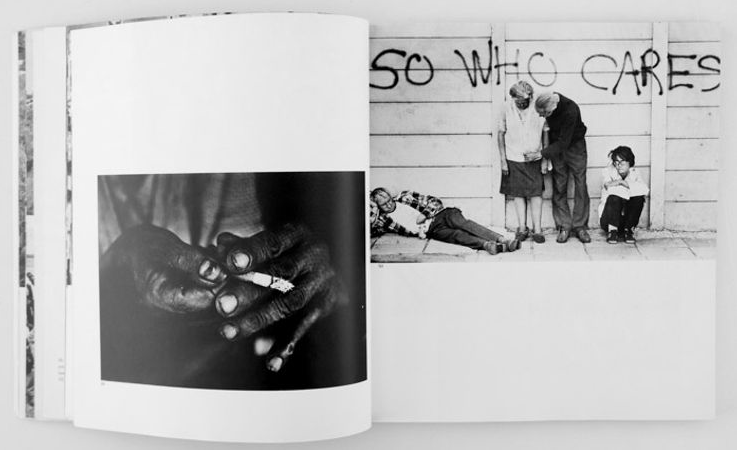

At the heart of Kuus’s work is the conviction that photography can be both journalism and testimony. His grainy, high-contrast images do not sanitize. Instead, they meet the viewer’s gaze with the same candor they extended to their subjects: a woman weeping over a demolished home; children playing in alleys watched by soldiers; protesters raising clenched fists against armored police vehicles. In each frame, Kuus offered a searing reminder that to document is to remember, and to remember is to resist.

The Beginnings of Collaboration

The partnership between Kuus and McDonald began almost by accident. Kuus, an Estonian-born South African photographer, had been chronicling township unrest for international wire services when his images caught the eye of McDonald, then a rising British broadcaster reporting on African affairs. What began as a plan for a single television documentary evolved into a deeper commitment to create a permanent visual archive. The pair shared a conviction that the world needed to see apartheid not as a passing headline but as a daily reality etched onto people’s bodies and lives.

That the book was swifty banned in South Africa spoke volumes about the state’s fear of images. Unlike text, which could be argued with or ignored, photography provided an immediate, incontrovertible truth. The suppression of South Africa in Black and White was an admission that the regime understood the power of the visual archive. To see was to know and to know was to undermine the elaborate machinery of propaganda.

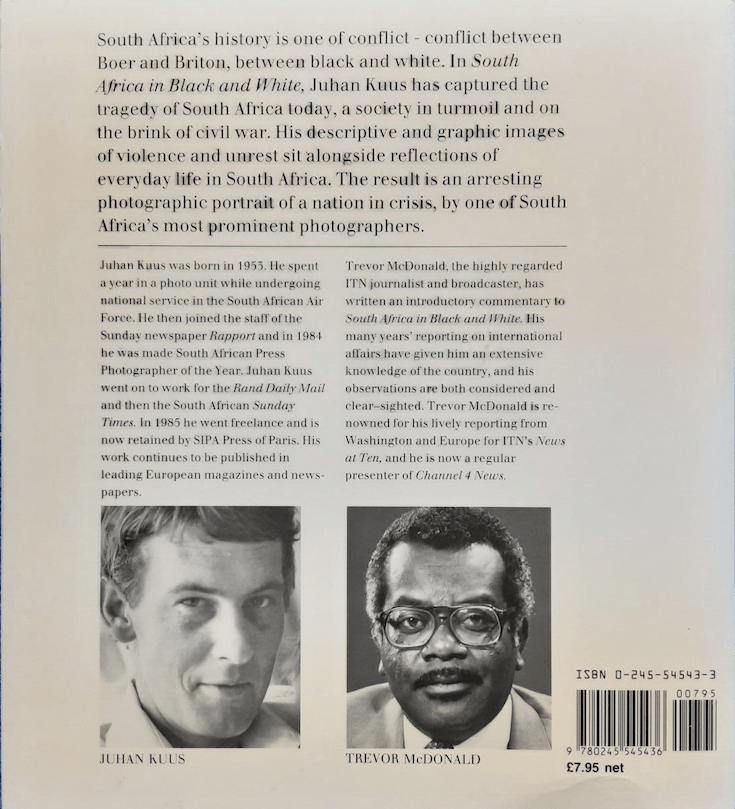

Trevor McDonald’s essays brought an outsider’s lens to the project, linking the local struggle to a global audience that often needed reminders that apartheid was not an abstraction but an everyday horror. McDonald’s narration threaded through the photographs, contextualizing the images within the broader currents of resistance, complicity, and international outrage. It was this pairing of a South African photographer and a British journalist that allowed the work to travel beyond the censors’ reach and rally international solidarity.

The book won several international accolades, including the World Press Photo Award for Kuus’s images, and cemented McDonald’s reputation as a formidable chronicler of injustice.

Margins in Focus

While protests, funerals, and political rallies formed the expected core of the collection, it was the images on the periphery that startled me most as a reader. In neighborhoods like Hillbrow, Kuus documented openly working male prostitutes, an inclusion that felt radical both then and now. Under a regime that criminalized Black existence and policed sexuality, the visibility of these men felt almost subversive. It reminded me that resistance was not always overt; sometimes it was the quiet insistence on claiming identity, pleasure, and livelihood against impossible odds.

Photographing human suffering is always an ethical tightrope. Kuus’s work is often raw, even harrowing, but it rarely crosses into exploitation. His subjects emerge as more than symbols; they remain complex individuals navigating a dehumanizing system. The tension between documenting trauma and honoring dignity is palpable in every frame, a testament to his commitment to truth without sensationalism.

Where They Are Now

Juhan Kuus continued to document social struggles in South Africa and beyond, though his later years were marked by financial hardship and struggles with mental health. He passed away in 2015. Trevor McDonald went on to become one of Britain’s most respected broadcasters, knighted for his services to journalism. Though separated by geography and circumstance, their collaboration endures as one of the most uncompromising visual records of apartheid.

The families depicted in the photographs some crouched in mourning, others confronting riot police faced uncertain futures after the crisis. With apartheid’s formal end in 1994, many of the communities Kuus photographed continued to grapple with poverty, unemployment, and the lingering trauma of dispossession. In interviews decades later, some survivors spoke of both pride and sorrow at seeing their images preserved: proof of what they endured, but also a reminder of promises still unfulfilled. The children in the photos are now middle-aged adults, some activists in their own right, others quietly rebuilding lives in townships still shaped by history’s deep wounds.

Decades later, the legacy of South Africa in Black and White endures in the work of contemporary African photographers and visual artists who have inherited and transformed this language of protest. From Zanele Muholi’s portraits of Black queer communities to the photojournalism emerging from student-led movements like #FeesMustFall, today’s practitioners build on Kuus’s belief in photography’s capacity to challenge power and restore visibility to the margins.

South Africa in Black and White is more than a historical artifact; it is a reminder of how art can be an instrument of resistance and a record of survival. In revisiting these images now, we are called not only to remember apartheid’s cruelties but to consider how systems of erasure persist and how photography can still illuminate, disrupt, and inspire.

Leave a comment